| Cutting the peat |

When I was much younger, my adult beverage of choice was Bourbon. Then, I discovered wine. My wine epiphany probably happened in Germany in the early 1950s, when I accidentally found there was more to drink than beer.

With this new discovery, my interest in Bourbon began to fade as I started to find and taste German and French wine. The unspoken rule, among my new wine friends held that if you were a wine person, you didn't drink any of the hard stuff.

Wine was for savoring and appreciating, they said, while Bourbon whiskey and other spirits were for getting a buzz on. Of course, that may have been true in the '50s, but today, Bourbon is a more interesting and varied tipple.

At the time, I considered myself to be the luckiest man alive. I was stationed in Bavaria, where some of the best beer in the world was brewed. So naturally I continued to enjoy the occasional beer, but exploring German white wine proved to be more interesting.

Eventually, I wondered if I had graduated to wine or was I just fooling myself? The move to wine sounded about right, so Bourbon was set aside.

Then, I discovered single malt Scotch whisky and the whole no spirits thing was resurrected. Back in my Bourbon days, Scotch did not have the same appeal as Bourbon whiskey, but my occasional dram was blended Scotch; single malts were just starting to make a comeback in Scottish distilling.

Sidebar: There is a slight difference in the spelling: The spirit distilled in Scotland and Canada is spelled "whisky," while the United States and Ireland prefer "whiskey."

Single malt whisky is different from blended Scotch, as different as a Bordeaux wine is from Burgundy. Blended Scotch (think Dewars, Johnnie Walker) is a base spirit and a selection of various single malts, blended to create a house style. A single malt is the product of a single distillery and may sometimes be used in a blend.

Blended Scotch has a sameness, while each single malt shows a different personality that come through in its layered flavors. The nuanced differences I found in a Highland single malt compared, for example, to a peaty Islay malt was a revelation.

It was this personality that I found much closer to wine than it was to any other spirit.

|

| Swan necks on copper pot stills |

I wanted to know more, like why Lowland single malts are lighter than Highland malts (it has to do with climate and terroir differences), why the source of the water used to ferment the barley is so important (distillers claim the mineral content and whether the water is soft or not, influence the flavor) and why the shape and age of the still defines the character of the whisky (that's a long explanation that is part science and part local whisky lore).

The more I learned about single malt whisky, the more I realized there are numerous parallels between whisky and wine. Here are a few examples:

* Legend and lore play a big role in the story of both wine and whisky. As mentioned above, back in the day, the shape, style and maintenance of the pot stills used to distill single malt whisky was based on lore. Today science explains why the shape of a still is important to the desired character of the spirit. If a copper panel wears thin, because of the continuous high heat in the still and must be replaced, the exact duplicate of the panel, including any dents in the old panel, is hammered into the replacement part.

* Both are made from a single natural crop: barley into whisky; grapes into wine.

* The environment (terroir) where grapes are grown defines the character of the wine. With whisky, the variety of barley and where it is grown, plus the source of the water used in the fermentation of the barley is the "terroir" of whisky making.

|

| Classic malting floor |

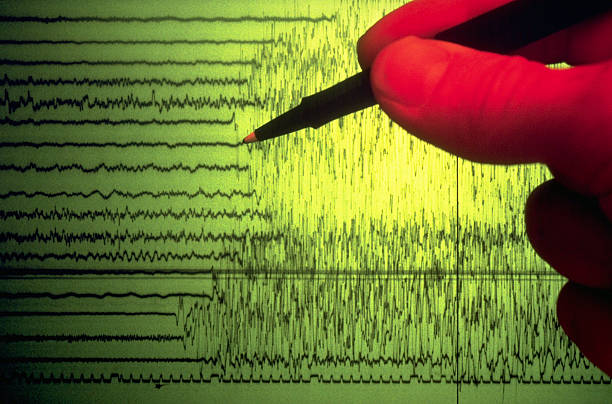

* Malting is a process where the barley is infused with smoke from a peat fire. The length of time the barley is malted depends on the style preferred by the distillery and the style of the region (i.e., island malts versus Highland malts). In general, Islay single malts are "peatier" than most other malts, but individual distillers may prefer more or less of the smoky character. As a process, malting is similar to the way grapes are processed in preparation for fermentation.

* The use of oak is an integral part of single malts as well as red wine and some white wines. The difference being that single malts are aged mainly in American oak, while red wine may be aged in a variety of oaks, including American. (This "oak rule" is changing as some whisky distilleries are experimenting with French oak.)

* Finally, there is a symbiotic relationship between single malt Scotch and wine. In recent years, single malt distillers began maturing their whiskies in barrels used previously to age wine. The Highland distillery Macallan has for years used ex-Sherry casks to age single malt; the Macallan 12-Year-Old, matured in Sherry wood, is a classic example of this practice.

Other single malt distilleries opted for barrels that previously held Port, Madeira, Sauternes, Bordeaux, Marsala and other oaks. Glenmorangie, a popular Highland malt whisky, offers a line of single malts aged in various ex-wine barrels, plus a selection of other aged single malts.

The trend to find a unique whisky and wine marriage has taken on many variations. The Dalmore Highland "Cigar Malt" starts the wood aging in American oak, then into former oloroso Sherry casks and is finished in Cabernet Sauvignon barrels. Auchentoshan "Three Wood" Lowland malt is aged in a mixture of Bourbon, oloroso Sherry and PX Sherry woods.

This brief essay has just scratched the surface of the pleasures of single malt whisky, Scotland's "wine."

Next blog: Light Reds

Contact me at boydvino707@gmail.com